Despite wet spring, wildfire still a threat

Next two weeks critical in potential for 2017-like fires

ENNIS - A stout snowpack and a wet spring have filled Madison County’s waterways and greened pastures to the point that some residents have said they haven’t seen things so verdant, so lush in nearly 50 years.

As a result, thoughts of last year’s drought and the fires it sparked are far, far away for most people.

But they shouldn’t be. The threat of fire is part and parcel of life here in Montana—a price we all pay for big sky scenery and wild spaces.

Current status

Madison County Director of Emergency Management Dustin Tetrault – he also wears the county’s fire prevention specialist hat – says the county is in the best shape he’s seen for the three years he’s been on the job here. This is the result of consistent June rainfall, with no dry periods, he said.

But that doesn’t mean Tetrault is kicking back, forgetting about fire risk.

While the snowpack and wet spring has been a boon for pastures, all that tall grass is a double-edged sword, Tetrault said. If we get hot, dry, breezy weather, that tall grass becomes fuel for fires to burn.

Tetrault is looking at the long run, seeing the potential for powerful fires due to this fuel load. If that happens, it will be later in the season: August or September, he said.

The next two weeks could be a critical time – either a restart to last year’s drought or the continuation of regular rainfall and limited fire risks.

“We’re not there yet,” he said. “but we could get back to it in 15 days of hot, dry, breezy weather, with no cool night cover. If that cures out all that grass, we could get right back into it. Missoula County right now has Stage No. 1, a burn ban. They didn’t have as much moisture as we got.”

2017 recalled

Last year was originally predicted to be a “below average fire season” for Montana. But 2017 quickly turned into a “challenging” season due to a phenomenon meteorologists call “flash drought.” It stayed hot and dry from June through October, sparking “uncharacteristically severe wildfire conditions” all over the state, according to the Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC).

Typically, says a summary of 2017 fires by DNRC Fire & Aviation Management Bureau Chief Mike DeGrosky, “fire season” begins in eastern Montana and moves west by August, with the eastern portion decreasing in activity as the summer progresses.

This was not the case in 2017: Statewide, some 1,300 fires burned more than 743,000 acres. People ignited 53 percent of these fires, 46 percent were lighting-sparked and the remainder had causes unknown.

That 1,300-fire figure represents more than triple the five-year average for fires. About 330 fires hit Montana annually, lighting up nearly 134,000 acres.

The first 2017 fire was mid-March. Then May brought a sharp change in conditions, especially in eastern Montana, where low precipitation, high temperatures and wind desiccated the landscape. Cattlemen culled their herds, and farmers saw only 20 percent of what they put into the ground sprouting.

Although a June 1 Water Supply Outlook Report showed snowpack totals above records in most Montana river basins, only a few low-elevation ranges had below normal snowpacks. Governor Bullock issued an executive order declaring a drought emergency for 18 counties and two Indian reservations in eastern Montana. Five days later, he declared a fire emergency for the entire state. And less than a month after that, that drought disaster reached 28 of 56 counties and five of seven reservations.

In July 2017, huge fires began. The second largest fire in Montana history, The Lodgepole Complex, in Garfield County, torched more than 270,000 acres. In August, the Sartin Draw fire (93,344 acres) and the Battle Complex fire (90,957 acres) burned more ground.

By September, 31 counties and six reservations were involved in the drought disaster – but not Madison County.

Regionally, 2017 had three big fires, all in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest:

• The Meyers fire burned more than 62,000 acres. First reported on July 17, 25 miles southwest of Phillipsburg, following a lightning storm, it burned chunks of Granite, Ravalli, Beaverhead and Deer Lodge counties, then merged with the Whetstone fire to consume more forest in early August. A heavy fuel load, exceptionally dry conditions, high heat and strong winds kicked up “explosive growth” in the Meyers fire during early September, which led to the evacuation of nearby communities.

• The Whetstone Ridge Fire, burned nearly 11,600 acres before the Meyers fire joined it.

• The Conrow Fire torched more than 2,700 acres following a lightning strike on August 24. The fire began on private land seven miles northeast of Whitehall, but grew when it moved onto Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and forest grounds in Jefferson County. Smoke from this and other fires created Butte’s worst air quality in two years. Altogether, this fire threatened 26 structures, including cellphone towers, mining areas, homes and cattle ranches.

The overall cost of the 2017 fire season was estimated at more than $96 million: $74 million in state money, $11 million for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), another $6 million for the National Guard and $5 million for Canadian air resources.

County fire plans

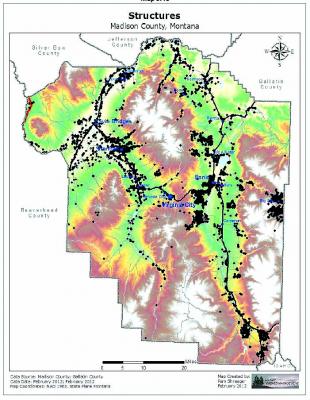

According to the Madison County Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP), a 2013 – 2014 document designed to “reduce the risk of a catastrophic wildland urban interface (WUI) fire,” fire is part and parcel of life here in Montana. It is up to residents to act appropriately and take precautions.

The CWPP was designed as a county planning tool, with objectives developed in 2000 with national fire planning efforts, as well as state rules that require local governments to consider fire issues.

The plan identified, inventoried and prioritized the risks associated with developing areas in Madison county and recommended educating county residents on strategies for living with fire. It also prioritized, promoted and provided direction for future mitigation and management strategies.

Some of the things the report found include:

• Land use – Growth from 1990 to 2010 changed land use in some areas from agriculture or undeveloped to residential. In 2007, for example, Madison County had 585 farms and 1 million acres of farm/ranch land, producing more than $53 million in agricultural sales (75 percent from livestock, 25 percent from crops.) By 2010, Madison County’s population jumped more than 14 percent, with many new residences built in various subdivisions around the county. Between 2004 and 2011, 1,400 lots were created from some 9,800 acres.

• Weather - Weather has a big impact on fire behavior, especially wind. Generally, moderate to strong southwest winds prevail in Madison county, exposing land sloped in this direction to more direct winds. Hence, fires typically spread southwest to northeast.

• Thunderstorm tracks – These also influence fires. A typical storm track begins along the southwestern edge of Madison County and tracks northeast, with any rain gone by the time it hits the northern half of the county. Meanwhile, lightning – especially dry lightning without accompanying rainfall, creates fires.

• Fire season – When summer’s “Bermuda high” weather patterns march across the southwest in July, low-level moisture is reduced but thunderstorm activity increases, making August a prime month for fire activity. Low humidity and heat can dry out fuels in as little as three days; this usually takes as long as five weeks. These “dry” thunderstorms also kick up wind and generate lightning – both key fire accelerators. Couple this with drought, and the potential for big fires ramps up. Consider 2012’s doozy of a fire season: The 5,100-acre Pony Fire, 10 miles west of Pony in the Tobacco Roots, started in late June and destroyed two residences, five outbuildings and a bridge. The fire was contained on July 8, but cost $4.7 million. Another big 2012 fire was Bear Trap No. 2, 20 miles northeast of Ennis along the Madison River. Fireworks started this blaze, also in late June, and it burned 10,800 acres of private land, 2,300 acres of BLM land, and 2,100 acres of state land. Structures were threatened and Highway 84 was closed for a time. The fire cost $1.2 million to contain.

• Suppression-related problems - Fire is normal in the West’s ecosystem. Low-intensity surface wildfires reduce fuel loads (dead and diseased trees, shrubs and grasses) and return nutrients to the soil. However, for about 100 years, fire suppression has allowed fuel loads to increase to “hazardous levels,” particularly in Madison County with its stands of mature Douglas fir and lodgepole pine. This, along with increased insect and disease, ups the odds for big fires a more frequent “fire return interval” (how often a location experiences fire). Except for high-elevation forests, the fire return interval has been exceeded throughout the Madison Watershed.

• Ignition risks – Fire data from DNRC, the BLM and the Forest Service says lightning and debris burning ignite most (75 percent) Madison County wildfires. Campsites (think campfires), unirrigated crop fields and highway corridors (think cigarettes tossed from a car window or vehicle sparks) were most likely to burn.

Future

“If history is any indication,” says the CWPP, “Madison County shall continue to see considerable new subdivisions. The county’s growth policy and subdivision regulations are the only existing avenues to manage local growth. Local government agencies that will be tasked to provide services for these areas need to participate in the subdivision review process and voice their infrastructure and mitigation requirements associated with this subdivision growth.”

“People moving into Madison County sometimes have a higher expectation of service than can be provided. Often, these expectations cannot be met in the rural areas due to a small tax base over a large area resulting in volunteer fire departments with aging equipment and limited training. For service delivery to match expectations, either significant modifications, including substantial tax increases, must be made, or public expectations need to become more realistic. As stated at the beginning of the plan, “Personal responsibility is key!”’

Tetrault’s suggestions for preventing fires are fairly simple.

“Big thing is any amount of lush grass, try to mitigate this where you can,” he said. “Graze it, mow it, use it as hay, keep the fuel load down. If lightning strikes this you’ve got fire.”

“Farmers and ranchers know this,” he continued, talking about the rich crop of hay currently being cut, another anticipated in August.

Tetrault also mentioned the grant money the county has available for “vegetative thinning,” and getting rid of junipers and sage,

“We work a lot on this,” he said. Most landowners work with a forester or contractor on fuels mitigation.

Information about this on the county website, visit https://madisoncountymt.gov/176/Emergency-Management-Fire-Warden.